Scratch that Itch

I've never wanted to push my kids into doing things, and especially not to do them the way that I do. I've always drawn, but I don't want to give my kids tutorials in how to draw 'the right way' or in my style.

I want them to have fun, and to figure things out, and if they want to do something, to learn it organically. I think that if they develop skills in this way, they'll have a deeper, more meaningful connection to their craft, and a sense of the 'why' that they might lack if I were to push any kind of a 'how' on them.

Limits and Creativity

Recently, my eight year old had less fun than you might expect in a school assignment about turning a book he's read into a breakfast cereal. This is about creativity, right? Have fun with it! But without a little framework to build on, it's difficult to be creative. There are too many possibilities, no hooks to hang your hat on. I broke down and did something I should have a long time ago, and we sat together at the drawing table.

In order to be creative, you need to have the freedom to make creative choices. In the same way that we all get too overwhelmed with everything from paying bills to planning meals for the family, you can set out to create something and sit frozen forever by endless considerations like medium, subject, and on and on.

This is why people often rely on prompts, or even why I often rely on irony and self-deprecation when I do my white board drawings at work. Anything can be a frame that limits enough of the external concerns that within this small, focused area, the ideas flow and take shape.

Trust the Algorithms

I showed my son some fun cereal boxes, and broke out the tried and true rule of thirds, and some common cropping techniques (e.g., don't show the whole bowl: let it sit mostly out of frame, and zoom in tight to show the details). We talked about how this or that design had a sense of movement or excitement based on simple principles, essentially common design algorithms that allow you to quickly put together a pleasing and familiar layout and focus on the details.

In no time, he pushed me aside and said he had an idea. A frustrating and tedious effort turned into a fun design.

Of course, algorithms aren't universals or hard and fast rules. You don't have to use the "rule" of thirds, but it's amazing how applying a simple tool like that can open things and free you to start making creative choices.

The Art of Code

It felt like a big win, and I decided to take that tack because of something that had recently happened while he was struggling with a problem on Scratch, MIT's awesome coding community aimed at kids.

What's most interesting to me about Scratch is that he's kind doing what I did when I was younger, either as a kid trying to figure out B.A.S.I.C. in the '80s or later as a young adult, viewing source in the '90s and learning how the web worked. He remixes a project, say a game that someone else has made — something from an older, more experienced, more savvy programmer — and he learns by building on that.

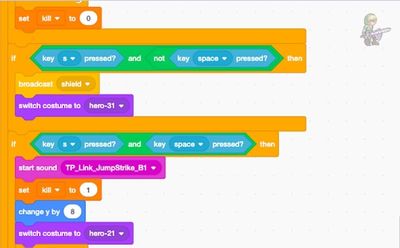

In this case, it was a little more complex than he was used to, with an NPC being generated by some action, and then removed upon another action. How do you add a new enemy when this one is defeated?

The details are less important than the principles. As he went back to the code and made tweaks, and failed to see the expected result, he grew more and more frustrated. This, too, was familiar. We've all been there, playing the game of tinkering till it works. But it's a dangerous game, and rarely actually works.

So now, instead of building on what's there, what he needed was to work out how to duplicate functionality as needed, and how to debug what's gone wrong.

At first, the code he added had no effect, and after asking him about the the specific actions that triggered various results, and the conditions under which certain things occurred, he was able to think through and locate the code that controlled the NPC and its appearance.

Well, not quite its appearance. But we were close. See, the NPC was definitely there, only we couldn’t physically see it. We could hear its sword, and our character took damage, but we just flat couldn’t see it. It was invisible.

Back to the code, and back to more questions about the conditions under which this or that happened helped my son to see where a costume was changed or the opacity of the sprite was set.

Before long, with a little guidance on thinking through the logic of the program rather than tinkering directly with the code, he was able to take a single enemy demo and turn it into a game with 14 levels of enemy combatants. (I might have gone with 3 to start, but he set it at 14, and I wasn't going to argue.)

I didn’t write any code for him, but stepped in with some very basic debugging knowledge to lighten his load and let him find the answers. It was incredibly rewarding for both of us, and it never approached a rote lesson in “how to code.” It was just a nudge in the right direction, and some boundaries that gave him the freedom to escape anxiety, find his way, and get back to the fun of making things.

I think an important lesson is that you have greater freedom to be creative and to learn when you have senior people around you who can clear away obstacles, put things in context, and nudge you in the right directions. This is true for kids, and it's true for junior developers. No one needs to reinvent the wheel or suffer in silence. But keep in mind that people don't always know which questions to ask, or what's in their way.

It's up to you to keep an eye out, and lend a hand where you can.