Number Ones — 1976

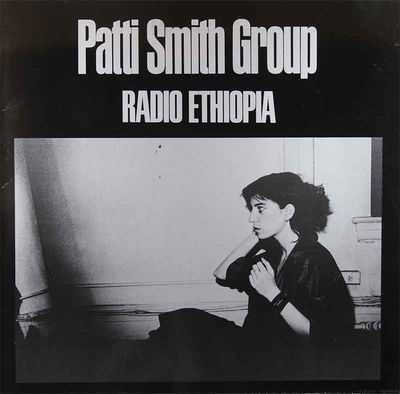

Radio Ethiopia by the Patti Smith Group was the best album of the bicentennial

Here's a rarity: something good that came out of Twitter. A while back somebody was tweeting about the best albums of their lifetime, one for each year they've been alive. I've been thinking about for probably a few months by now, and it's been a long series of tough choices, but it's also been rewarding and helped me to discover things I can't believe I ever lived without.

For the year of my birth — I made the bicentennial by just a few weeks — I flirted with the Ramones, and wanted so badly to go with the Modern Lovers. But to be fair to the spirit of the game here, that incarnation of the Modern Lovers was long gone and the recordings were made four or more years before I was born. It's always tempting to think of Bowie, but as great as he was, it's also impossible to pick the dawning of the Thin White Duke, with Bowie in the midst of a cocaine-fueled dalliance with fascism. And even though I firmly believe there'd be no Velvet Underground, and then no Modern Lovers, without Bob Dylan, and as great as Desire is, Mozambique is a little too goofy for this honor.

For the later years of the exercise I considered PJ Harvey here and there, and she was often a close second or third. When I discovered her music in the '90s, I had no idea Polly Jean was sonically and spiritually a latter-day Patti Smith. Listening to Smith's 1976 sophomore album, Radio Ethiopia, is an eerie experience for a PJ Harvey fan. It's not just a gendered equation, which is an easy and unfair trap to fall into, filing artists away into silos and patting yourself on the back for recognizing a representative minority here and there while seeing diversity in the sea of faces like your own that fill your shelves. Harvey shares vocal qualities with Smith, and at every turn, from her emotive delivery to the peculiarities of her phrasing, she seems to evoke Patti Smith, and never more closely than from the performances on Radio Ethiopia.

Radio Ethiopia

And Radio Ethiopia is a weird album in a couple of ways. It's variously described as less accessible than Horses on the one hand and an effort to sell-out and achieve commercial success on the other. These can't both be true, and I think the reason is partly that Smith had a sensibility that ranged beyond the abilities and experience of most rock critics, at a time when rock journalism was still pretty young. She's described by some as self-indulgent and lacking direction, and critics sometimes obsess over a "heavy" guitar sound, in a way that feels vaguely like cries of "Judas!" against Dylan. But who could be surprised by "hard rock" when Smith wrote lyrics for Blue Oyster Cult?

One song puts to rest any claims of selling out, and it's one that feels the most commercial, till it eats itself alive and births something bizarre. Poppies opens as just the kind of rolling, jazzy number you'd expect from an album produced by a New York band in the mid-70s. But as it approaches the mid-point, competing versions of Patti Smith take turns stealing the song from each other, chanting, wailing, rambling, evocative of Bob Dylan, Jim Morrison and maybe even a little Leonard Cohen. It's been called schizophrenic, but it fucks me up how perfect it is in the end.